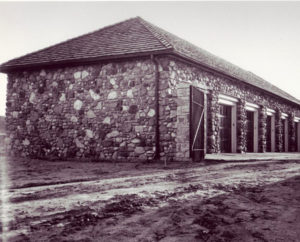

Original House

It is hard to believe the Highlands Ranch Mansion began as a small stone farmhouse on the isolated plains of early northern Douglas County.

Built in 1891 by a Pennsylvania man named Samuel Allen Long, the original building measured about 30 feet by 50 feet and featured a traditional gabled roof, a one and one half story upstairs bedroom space, and a front porch with an overhang. Long called his home and surrounding farm “Rotherwood” after another farm he admired during his childhood. He carved this name in the stone above the front doorway of his home and the construction year “1891” just below an upstairs window. Visitors to the Mansion can find these two carvings by simply looking upward when entering the building through what is referred to today as the Rotherwood door.